- a. What are the topics most and least commonly studied in the literature on identity fraud victimization?

- b. What are the risks of bias associated with existing studies?

- c. What do studies with lower risk of bias and/or higher quality demonstrate about key concepts studied by these studies?

By answering these questions, this review primarily aims to provide suggestions for future research on identity fraud victimization including potential research questions for future systematic reviews as the evidence base on this topic becomes denser at which point researchers can conduct larger knowledge syntheses. Accordingly, although risk of bias and quality of studies are assessed for each study included in this review, a meta-analysis or statistical pooling of studies has not been performed.

Definitional issues regarding identity theft

There is an increased interest in the field to differentiate between the terms of identity theft and identity fraud because not all identity theft incidents involve a fraudulent act at the time of theft of personal information. Javelin Strategy and Research (2021) defines identity theft as “unauthorized access of personal information” and identity fraud as identity theft incidents in which there is an element of financial gain. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the BJS define identity theft as “fraud that is committed or attempted using a person’s identifying information without authority” (FTC, 2004; Harrell, 2019, p. 18). The acts considered by the BJS under this definition include unauthorized use or attempted use of an existing account, unauthorized use or attempted use of personal information to open a new account, and misuse or attempted misuse of personal information for a fraudulent purpose (Harrell, 2019).

Researchers differentiated between three stages of identity theft: acquisition of personal information, use of personal information for illegal financial or other gain, and discovery of identity theft (Newman & McNally, 2007). Personal information can be acquired through different means ranging from simple physical theft to more complex and even legal ways such as scams, cyber, or mechanical means and purchasing the information from data brokers. The acquired personal information is used for financial gain or other criminal purposes (Newman & McNally, 2007). However, fraudulent use of information might not happen at the time of acquiring of information and once personal information is exposed, a person can become an identity theft victim multiple times.

Another important stage of identity theft is the discovery of theft of personal information and associated frauds because the longer the discovery period is the less likely it is for victims to contact law enforcement (Randa & Reyns, 2020) and the more likely it is for them to experience aggravated consequences (Synovate, 2007). Police reports are critical for victims to pursue an identity theft case (OVC, 2010). For victims of certain forms of identity theft, the discovery of victimization can take as long as 6 months or more (Synovate, 2003, 2007). In cases where personal information is exposed due to data breaches, victims might have greatly varying experiences of when and what they learn about this exposure (if at all) and the services available to them. Currently, all 50 states, the District of Columbia, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands have laws requiring businesses, and in most states, government organizations to notify individuals of security breaches involving personal information (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2022). However, the decisions of organizations on whom to notify (such as the victims, the FTC, or law enforcement), when to notify, and how to notify can drastically vary from one geography to another based on laws. Two groups can become targets of identity fraud: individuals whose personal information is stolen and organizations which are in care of the stolen personal information or which become targets of fraud. Law enforcement might be more likely to put emphasis on organizations as visible and collective targets of identity theft (Newman & McNally, 2005).

In recognition of the stages and targets of identity theft, there has been an interest in the field to differentiate between the terms of identity theft and identity fraud. In popular knowledge, the terms “identity theft” and “identity fraud” have been used interchangeably considering the interrelated nature of acts considered under these terms. However, it is acknowledged that these terms legally refer to different things (Newman & McNally, 2005).

In statute, identity theft was legally defined at the federal level with the Federal Identity Theft and Assumption Deterrence Act (ITADA) of 1998 (Newman & McNally, 2005). ITADA made it a federal offense to “knowingly transfer or use, without lawful authority, a means of identification of another person with the intent to commit, or to aid or abet, any unlawful activity that constitutes a violation of Federal law, or that constitutes a felony under any applicable State or local law” (the Identity Theft Act; U.S. Public Law 105-318). Prior to this legal definition of identity theft in the US, the terms “identity theft” and “identity fraud” were used to primarily distinguish between the individual victims and collective victims with the former being referred to as victims of identity theft and the latter as victims of identity fraud (McNally & Newman, 2008). In later years, these terms have been used to differentiate between the act of unlawful acquisition of identity information and the fraudulent use of personal information.

Over the years, different research and practice sources have generally considered the following acts under identity theft and identity fraud: criminal identity theft in which individuals use others’ personal information during interactions with law enforcement or for committing other crimes (Button et al., 2014); existing account frauds where an individual makes unauthorized charges to existing accounts such as bank, credit card, and other existing accounts; medical/insurance identity theft in which an individual fraudulently uses somebody else’s personal information to receive medical care; new account frauds in which an individual’s personal information is used unlawfully to open a new account; social security number (SSN) related frauds in which an individual uses the victim’s SSN to file for a tax return, for employment, or to receive government benefits; and synthetic identity theft in which different pieces of real and fake identity information are combined together to create an identity and to commit frauds (Dixon & Barrett, 2013; FTC, 2017, 2018; GAO, 2017; Pierce, 2009).

The opportunity structure for identity theft

Earlier research on perpetrators of identity theft, using a conceptual framework informed by Cornish and Clarke’s (1986) Rational Choice Theory and the methodology of crime script analysis, has focused on the motivations and methods of committing identity frauds (see Copes & Vieraitis, 2009, 2012) and the impact of experiences of perpetrators’ on their criminal involvement and criminal event decisions (Vieraitis et al., 2015). Regarding the organizational level of identity frauds, research has shown that perpetrators of identity theft and fraud might range from individuals to street-level and more advanced criminal organizations (Copes & Vieraitis, 2009, 2012; Newman & McNally, 2007). Although earlier research has shown that perpetrators of identity theft used low-technology methods (Copes & Vieraitis, 2009, 2012), perpetrators of identity theft have started using more complex schemes and relying more heavily on the internet to acquire identity information over the years (Pascual et al., 2018).

The number of identity fraud victims who know the perpetrators has decreased over the years. For instance, in 2008, about 40% of identity fraud victims knew how the incident happened, and from those, about 30% believed that their information was stolen during a purchase or other interaction and 20% believed that their personal information was stolen from their wallet, 14% believed the information was stolen from files at an office, and another 8% believed that the information was stolen by friends or family (Langton & Planty, 2010). In 2012, about 32% of identity victims in the US knew how their personal information was stolen and 9% knew the identity of the perpetrator (Harrell & Langton, 2013). Comparatively, in 2018, 25% of identity fraud victims knew how the offender obtained the information and 6% of victims knew something about the perpetrator (Harrell, 2021). This unknown status of how the information is obtained or who the perpetrator is sometimes interpreted as the technology-facilitated nature of the acquisition of information (Newman & McNally, 2005). However, victims of instrumental identity theft in which an individual’s information is stolen to commit other frauds and crimes, and individuals who have been victims of multiple types of identity theft in the recent past, are more likely to know how their information was stolen and the perpetrator (Harrell, 2019). New research examining the impact of the pandemic on identity fraud further suggest an increase in identity fraud scams and loan fraud in which perpetrators directly target consumers and a significant portion of victims of identity fraud scams and loan fraud (about 3 in every 4 victims) knowing their perpetrators (Buzzard & Kitten, 2021).

The most frequent way identity theft victims become known to authorities in the US is complaints to financial institutions (Harrell, 2021). The other ways victims report their victimization include complaints to federal institutions [such as the FTC and the Internet Crimes Complaint Center (IC3)] and non-governmental organizations [such as the Identity Theft Resource Center (ITRC) and the National Consumers League (NCL)] and crime reports to law enforcement.

In the past decade, federal and non-profit organizations increased their efforts to educate consumers on risks and reporting of identity theft and how to deal with the ramifications of fraud victimization. Several federal and other organizations provide information for services victims can receive such as reporting and assistance hotlines, civil and criminal legal services, and trauma informed counseling. Other available responses to identity theft include credit and identity theft monitoring, identity theft insurance, and identity theft restoration; however, these responses are typically provided by for-profit companies. Depending on who the victim contacts, victims might not be uniformly informed about all options available to them. Many victim service providers working in organizations funded by the Victims of Crime Act do not have the resources to recognize and respond to fraud’s harms (OVC, 2010). Furthermore, even when services are available, there might be significant barriers against victims’ access to these resources including financial barriers. Currently, majority of services available to identity theft victims are geared towards handling out-of-pocket expenses.

At the time of this review, there was a fast evolving opportunity structure for identity theft and identity fraud due to the hardships inflicted on individuals by the economic and health crises. Direct stimulus payments, increased loan applications, and the overall increase in online activities during the pandemic have provided increased opportunities for identity frauds such as account takeovers (Tedder & Buzzard, 2020) and identity frauds in relation to scams (Buzzard & Kitten, 2021). Furthermore, low-income individuals, older individuals, individuals who depend on others for their care, and individuals who might not have control over their finances can experience aggravated harms as a result of identity fraud victimization. Furthermore, some victims might experience a significant damage to their reputations (Button et al., 2014). All of these conditions necessitate more scientific inquiry and a better understanding of existing research evidence base on identity fraud.

Scope of review

This review focuses only on identity fraud victimization and excludes studies that focus on theft of personal information but not the fraud aspect of identity theft. As an example, although skimming, intentional data breaches, and mail theft are acts of identity theft, if a research study focused solely on these acts but not the fraud aspect, that study was excluded from the review. The review further excluded research on identity frauds targeting organizations and governments, harms of identity fraud to businesses and institutions, and research studies focusing on victims in countries other than the US. The review also excluded sources in which no data collection and analysis was attempted, paid research content, and research summaries with limited or no information about methodology.

The current review included empirical research studies that focus on identity fraud victimization in the US which were published in English and between January 2000 and November 2021. The resources that were reviewed included journal articles, PhD dissertations, government reports, and other reports found in major social science research databases and on websites of organizations focusing on identity theft. This review adopted a broad definition of “empirical” research focusing on studies using both quantitative and qualitative data analysis methods including descriptive analysis.

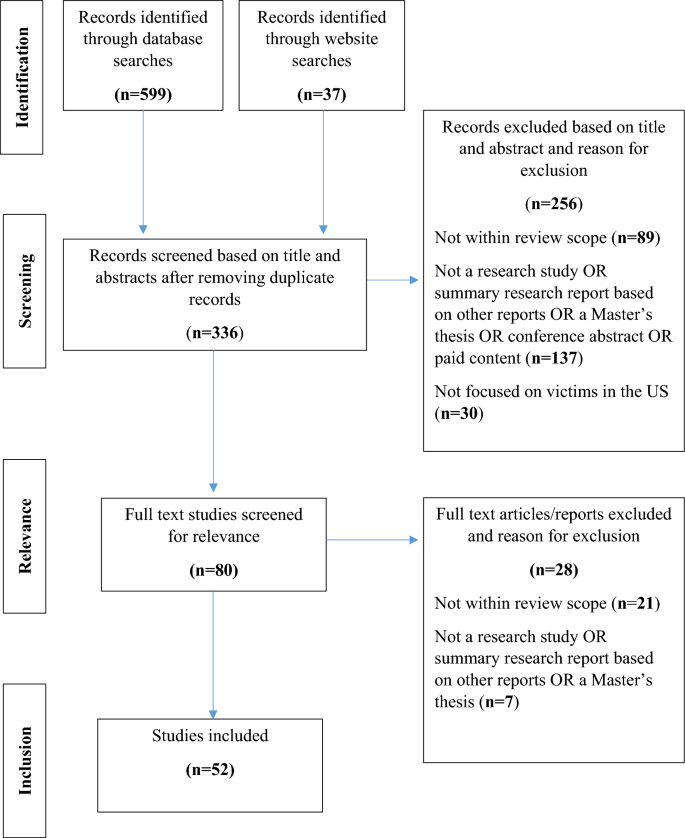

In this review, a comprehensive search strategy was used to search the literature for relevant studies. The search strategy was consisted of (1) a formal search of academic databases using search strings based on Boolean operators Footnote 1 and (2) an informal search of grey literature using keyword searches and searches on the websites of organizations focusing on identity fraud. Searches were conducted in the following academic databases: Proquest Social Sciences Collection, Web of Science Social Sciences Citation Index, Wiley Online, JSTOR, Criminal Justice Abstracts, SocIndex Full text, and Violence and Abuse Abstracts. Additional searches were completed on the websites of the BJS, the Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3), the FTC, the ITRC, Javelin, the National White Collar Crime Center (NW3C), and the Ponemon Institute.

299 potential studies were identified through database searches (excluding duplicate records) and 37 publicly available empirical studies were identified from websites of leading organizations on identity fraud. Ultimately, 29 sources from these database searches and 23 sources from the aforementioned organizations met the inclusion criteria for this review (see Appendix 1 for the screening process). These included articles are denoted with an asterisk (*) in the references section.

Appraisal of quality of studies

Studies included in this review were appraised for methodological quality. Quality appraisal was conducted after deeming a study eligible for the review based on the inclusion criteria specified earlier. Appendix 2 and Appendix 3 show the two quality appraisal tools that were adapted from Hoy et al. (2012) and Mays and Pope (2020). Each quantitative study was assigned into one of three categories based on the evaluation of risk of study bias: low, moderate, or high risk of bias. Each qualitative study was assigned into one of three categories based on the evaluation of quality: low, medium, or high quality. For the only mixed-method study in this review, risk of bias and study quality were evaluated separately for qualitative and quantitative elements of the study. More information about quality rating process and quality ratings of studies can be found in Appendix 4 and notes on bias and quality assessments for included studies can be found in Appendix 5.

Trends of identity fraud victimization research

Of the 52 studies included in this review, the majority were NGO reports (n = 22) followed by journal articles (n = 18), government reports (n = 7), and PhD dissertations (n = 5). Almost all of the white papers from government organizations and NGOs (n = 28) were descriptive quantitative studies. All of the white papers included in this review (n = 29) were based on survey data. Of the 23 academic studies (i.e., journal articles and dissertations) included in the review, 19 quantitative studies used surveys and 4 qualitative studies used interviews or focus groups discussions as their data source. Among these 23 academic studies, the primary data analysis method was regression analysis (n = 15) followed by descriptive quantitative data analysis (incidence, correlation, ANOVA analyses (n = 4), narrative analysis (n = 3), and phenomenological analysis (n = 1). Only one quantitative study included in this review used a quasi-experimental design with propensity score matching, and none of the quantitative studies included in the review had random assignment. The earliest journal article included in this review was published in 2006 and half of the journal articles included in this review (n = 9) were published between 2019 and 2021 (n = 9).

The studies in this review thematically fell into one or more of the following four areas of identity fraud victimization research: (1) prevalence, incidence, and reporting, (2) risk factors, (3) harms, and (4) prevention, programs, and services. From the 52 studies included in this review, 31 focused on harms, 22 focused on prevalence, incidence, and reporting, and 15 focused on risk factors. Notably, only 3 studies included in this review focused on services for identity fraud victims and among these studies there were no experiments with random assignment focusing on the effectiveness of specific programs or interventions for identity fraud victims (see Table 1 for subtopics and citations of identity fraud studies included in this review).

Appendix 2

Hoy et al. (2012) risk of bias tool

Note: If there is insufficient information in the article to permit a judgment for a particular item, please answer No (HIGH RISK) for that particular item.

Risk of bias item

Criteria for answers

External validity

1. Was the study’s target population a close representation of the national population in relation to relevant variables?

• Yes (LOW RISK): The study’s target population was a close representation of the national population

• No (HIGH RISK): The study’s target population was clearly NOT representative of the national population

2. Was the sampling frame a true or close representation of the target population?

• Yes (LOW RISK): The sampling frame was a true or close representation of the target population

• No (HIGH RISK): The sampling frame was NOT a true or close representation of the target population

3. Was some form of random selection used to select the sample, OR, was a census undertaken?

• Yes (LOW RISK): A census was undertaken, OR, some form of random selection was used to select the sample (e.g., simple random sampling, stratified random sampling, cluster sampling, systematic sampling)

• No (HIGH RISK): A census was NOT undertaken, AND some form of random selection was NOT used to select the sample

4. Was the likelihood of non-response bias minimal?

• Yes (LOW RISK): The response rate for the study was > / = 75%, OR, an analysis was performed that showed no significant difference in relevant demographic characteristics between responders and nonresponders

Internal validity

5. Were data collected directly from the subjects (as opposed to a proxy)?

• Yes (LOW RISK): All data were collected directly from the subjects

• No (HIGH RISK): In some instances, data were collected from a proxy

6. Was an acceptable case definition used in the study?*

• Yes (LOW RISK): An acceptable case definition was used

• No (HIGH RISK): An acceptable case definition was NOT used

7. Was the study instrument that measured the parameter of interest shown to have reliability and validity (if necessary)?

• Yes (LOW RISK): The study instrument had been shown to have reliability and validity (if this was necessary), e.g., test–retest, piloting, validation in a previous study, etc

• No (HIGH RISK): The study instrument had NOT been shown to have reliability or validity (if this was necessary)

8. Was the same mode of data collection used for all subjects?

• Yes (LOW RISK): The same mode of data collection was used for all subjects

• No (HIGH RISK): The same mode of data collection was NOT used for all subjects

9. Was the length of the shortest prevalence period for the parameter of interest appropriate?*

• Yes (LOW RISK): The shortest prevalence period for the parameter of interest was appropriate (e.g., point prevalence, one-week prevalence, one-year prevalence)

• No (HIGH RISK): The shortest prevalence period for the parameter of interest was not appropriate (e.g., lifetime prevalence)

10. Were the numerator(s) and denominator(s) for the parameter of interest appropriate?*

• Yes (LOW RISK): The paper presented appropriate numerator(s) AND denominator(s) for the parameter of interest

• No (HIGH RISK): The paper did present numerator(s) AND denominator(s) for the parameter of interest but one or more of these were inappropriate

11. Summary item on the overall risk of study bias

• LOW RISK OF BIAS: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate

• MODERATE RISK OF BIAS: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate and may change the estimate

• HIGH RISK OF BIAS: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate and is likely to change the estimate

- *All descriptive quantitative studies were evaluated based on items 1–5, 7(if necessary), and 8. Items 6, 9, and 10 were only used to assess the risk of bias within prevalence studies

Appendix 3

Mays and Pope (2020) framework for assessing quality of qualitative studies

Features/processes of the study

Quality indicators (i.e., possible features of the study for consideration)

1. How credible are the findings?

Findings are supported by data/study evidence

Findings ‘make sense’; i.e., have a coherent logic

Findings are resonant with other knowledge

Corroborating evidence is used to support or refine findings (other data sources or other

2. How has knowledge or understanding been extended by the research?

Literature review summarizing previous knowledge and key issues raised by previous research

Aims and design related to existing knowledge, but identify new areas for investigation

Credible, clear discussion of how findings have contributed to knowledge and might be

applied to policy, practice, or theory development

Findings presented in a way that offers new insights or alternative ways of thinking

Limitations of evidence discussed and what remains unknown or unclear

3. How well does the study address its original aims and purpose?

Clear statement of aims and objectives, including reasons for any changes

Findings clearly linked to purposes of the study

Summary/conclusions related to aims

Discussion of limitations of study in meeting aims

4. How well is the scope for making wider inferences explained?

Discussion of what can be generalized to the wider population from which the sample was

drawn or cases selected

Detailed description of the contexts in which the data were collected to allow assessment of

applicability to other settings

Discussion of how propositions/findings may relate to wider theory and consideration of

Evidence supplied to support claims for wider inference

Discussion of limitations on drawing wider inferences

5. How defensible is the research design?

Discussion of how the overall research strategy was designed to meet the aims of the study

Discussion of rationale for study design

Convincing argument for specific features/components

Use of different features and data sources evidence in findings presented

Discussion of limitations of design and their implications for evidence produced

6. How well defended is the sample design or target selection of cases/documents?

Description of study locations, and how and why chosen

Description of population of interest and how sample selection relates to it

Rationale for selection of target sample, settings or documents

Discussion of how sample/selections allowed necessary comparisons to be made

7. How well is the eventual sample composition/case inclusion described?

Detailed description of achieved sample/cases covered

Efforts taken to maximize inclusion of all groups

Discussion of any missing coverage in achieved samples/cases and implications for study

Documentation of reasons for non-participation among sample approached or cases

Discussion of access and methods of approach, and how these might have affected coverage

8. How well were the data collected?

Discussion of who collected the data; procedures and documents used; checks on origin,

status, and authorship of documents

Audio- or video-recording of interviews, focus groups, discussions, etc. (if not, were

justifiable reasons given?)

Description of conventions for taking field notes

Description of how fieldwork methods may have influenced data collected

Demonstration, through portrayal and use of data. that depth, detail, and richness were

achieved in collection

9. How well has the analysis been conveyed?

Description of form of original data (e.g., transcripts, observations, notes, documents, etc.)

Clear rationale for choice of data management method, tools, or software package

Evidence of how descriptive analytic categories, classes, labels, etc. were generated and used

Discussion, with examples, of how any constructed analytic concepts, typologies, etc. were

devised and used

10. How well are the contexts of data sources retained and portrayed?

Description of background, history and socioeconomic/organizational characteristics of study

Participants’ perspectives/observations are placed in personal context (e.g., use of case studies,

vignettes, etc. are annotated with details of contributors)

Explanation of origins of written documents

Use of data management methods that preserve context (i.e., facilitate within case analysis)

11. How well has diversity of perspectives and content been explored?

Discussion of contribution of sample design/case selection to generating diversity

Description of diversity/multiple perspectives/ alternative positions in the evidence

Evidence of attention to negative cases, outliers or exceptions (deviant cases)

Typologies/models of variation derived and discussed

Examination of reasons for opposing or differing positions

Identification of patterns of association/linkages with divergent positions/groups

12. How well has detail, depth and complexity (i.e., richness) of the data been conveyed?

Use and exploration of contributors’ terms, concepts and meanings

Portrayal of subtlety/intricacy within data

Discussion of explicit and implicit explanations

Detection of underlying factors/influences

Identification of patterns of association/conceptual linkages within data

Presentation of illuminating textual extracts/observations

13. How clear are the links between data, interpretation and conclusions?

Clear conceptual links between analytic commentary and presentation of original data (i.e.

commentary relates to data cited)

Discussion of how/why a particular interpretation is assigned to specific aspects of data, with

illustrative extracts to support this

Discussion of how explanations, theories, and conclusions were derived; how they relate to

interpretations and content of original data; and whether alternative explanations were

Display of negative cases and how they lie outside main propositions/theory; or how

propositions/theory revised to include them

14. How clear and coherent is the reporting?

Demonstrates link to aims/questions of study

Provides a narrative or clearly constructed thematic account

Has structure and signposting that usefully guide reader

Provides accessible information for target audiences

Key messages are highlighted or summarized

Reflexivity and neutrality

15. How clear are the assumptions, theoretical perspectives and values that have shaped the research and its reporting?

Discussion/evidence of main assumptions, hypotheses and theories on which study was

based and how these affected each stage of the study

Discussion/evidence of ideological perspectives, values, and philosophy of the researchers

and how these affected methods and substance of the study

Evidence of openness to new/alternative ways of viewing subject, theories, or assumptions

Discussion of how error or bias may have arisen at each stage of the research, and how this

threat was addressed, if at all

Reflections on impact of researcher(s) on research process

16. What evidence is there of attention to ethical issues?

Evidence of thoughtfulness/sensitivity to research contexts and participants

Documentation of how research was presented in study settings and to participants

Documentation of consent procedures and information provided to participants

Discussion of how anonymity of participants/sources was protected, if appropriate or

Discussion of any measures to offer information, advice, support, etc. after the study where

participation exposed need for these

Discussion of potential harm or difficulty caused by participation and how avoided

17. How adequately has the research process been documented?

Discussion of strengths and weaknesses of data sources and methods

Documentation of changes made to design and reasons; implications for study coverage

Documents and reasons for changes in sample coverage, data collection, analysis, etc. and

Reproduction of main study documents (e.g., interview guides, data management

frameworks, letters of invitation)

Appendix 4

Quality/risk of bias evaluations and ratings for included studies

Evaluation of quantitative studies

This review adopted criteria from Hoy et al.’s (2012) risk of bias evaluation tool (see Appendix 2) to evaluate the risk of bias within quantitative studies. Hoy et al.’s (2012) risk of study bias assessment, similar to the GRADE approach, does not include a numerical rating but rather evaluates the overall risk of bias based on assessment of risk of bias of individual risk items (Hoy et al., 2012). Each quantitative study in this study was assigned into one of the following three categories based on an overall evaluation of risk of study bias based on this tool: low risk of bias, moderate risk of bias, or high risk of bias (see below for individual study ratings and Appendix 5 for bias/quality notes).

Evaluation of qualitative studies

Seventeen appraisal questions from Mays and Pope (2020) were used to evaluate the quality of qualitative studies based on the reporting of findings, study design, data collection, analysis, reporting, reflexivity and neutrality, ethics, and auditability of the studies (see Appendix 3). In this review, each qualitative study was allocated into one of the following three categories based on an overall evaluation of the study quality based on these 17 indicators: low quality, medium quality, or high quality (see below for individual study ratings and Appendix 5 for bias/quality notes).

Evaluation of mixed-method studies

For the only mixed-method study included in this review (see ITRC, 2003), the risk of bias and the study quality were evaluated separately for qualitative and quantitative elements of the study utilizing the frameworks by Hoy et al. (2012) and Mays and Pope (2020) (see below for individual study rating and Appendix 5 for bias/quality notes).